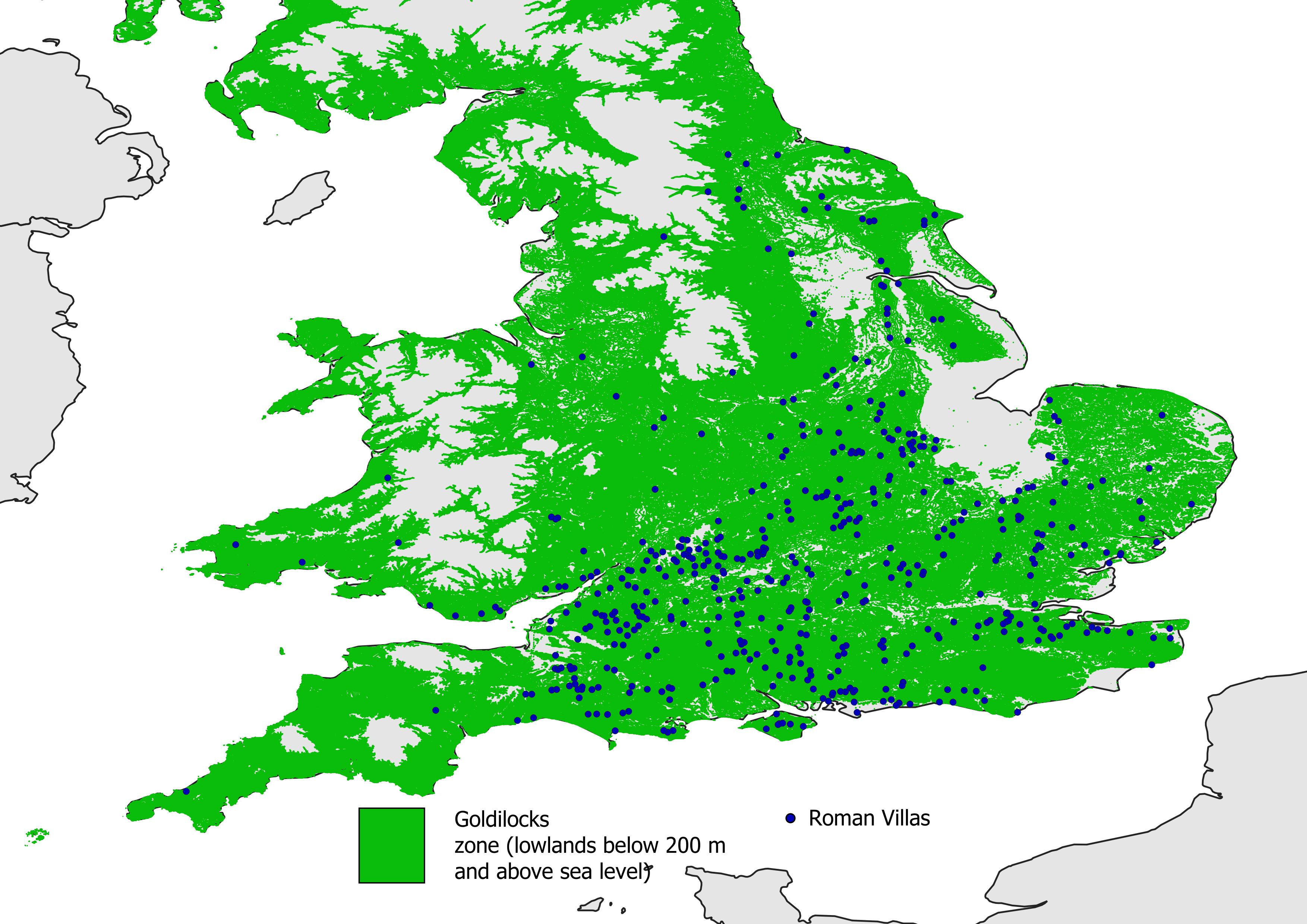

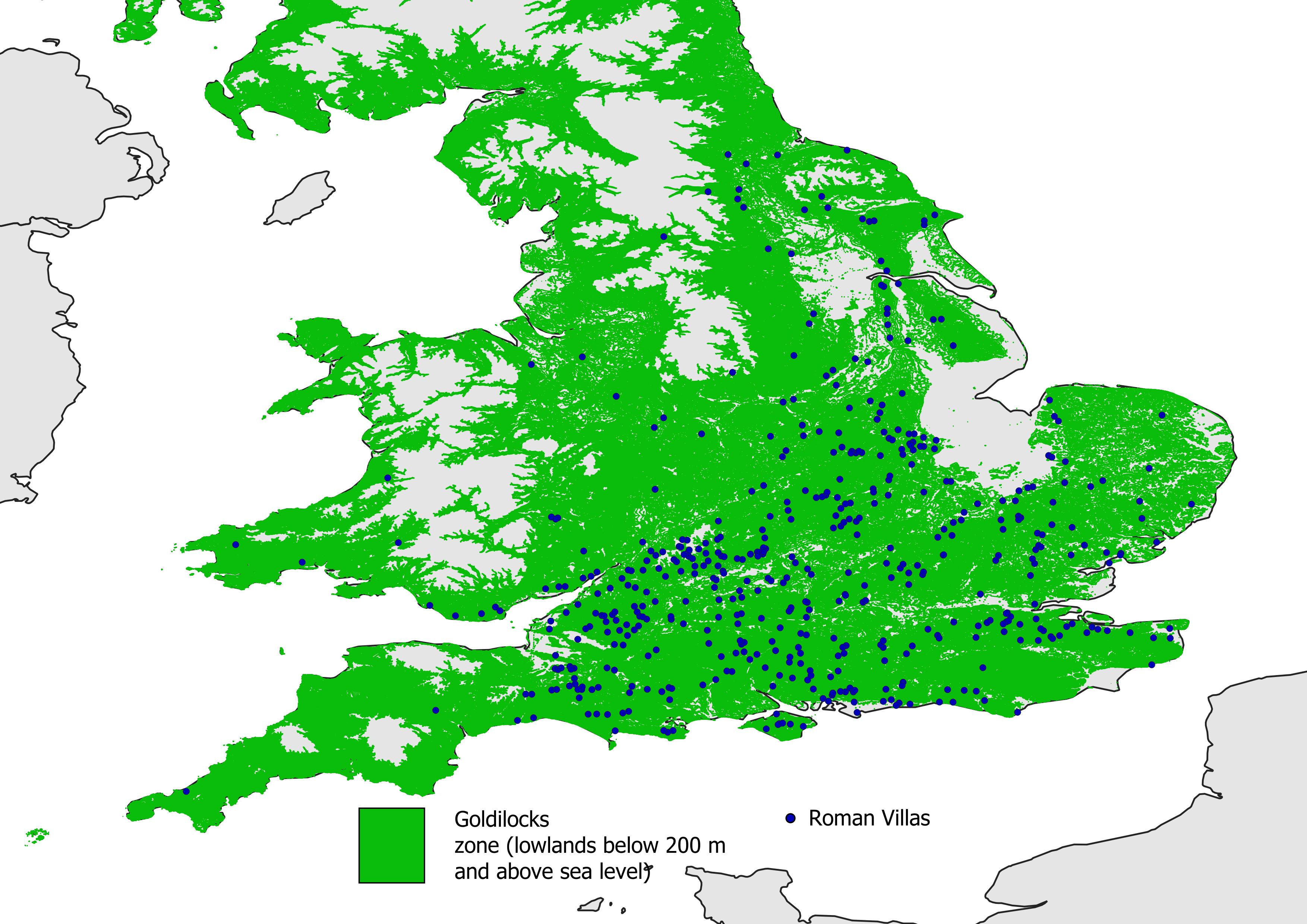

Figure 1 Showing the Distribution of Roman Villas in Relation to the Goldilocks Zone

I used to think of Roman Villas as rather special country houses for Roman officials. That’s partly true, they were indeed far more luxurious than the earlier Iron Age round houses, but they were much more. They were the administrative hubs of agricultural estates, complete with accommodation, barns, and even corn driers (Applebaum 1958, 67). Some villas were built on the site of earlier Iron Age farms, which remained the basic unit of agriculture elsewhere.

Not all land was suitable for Roman agriculture. Villas tended to avoid the coastal lowlands, which would have been flooded for most of the year; they also tended to avoid the poorer soils and cooler climate of the uplands. Figure 1 shows a Goldilocks zone, where most villas can be found. But, to be suitable was not enough. For example there are few Villas in East Anglia, Wales, the Midlands, the South-West peninsula, and generally north of the Severn-Humber line.

Figure 1 Showing the Distribution of Roman Villas in Relation to the Goldilocks Zone |

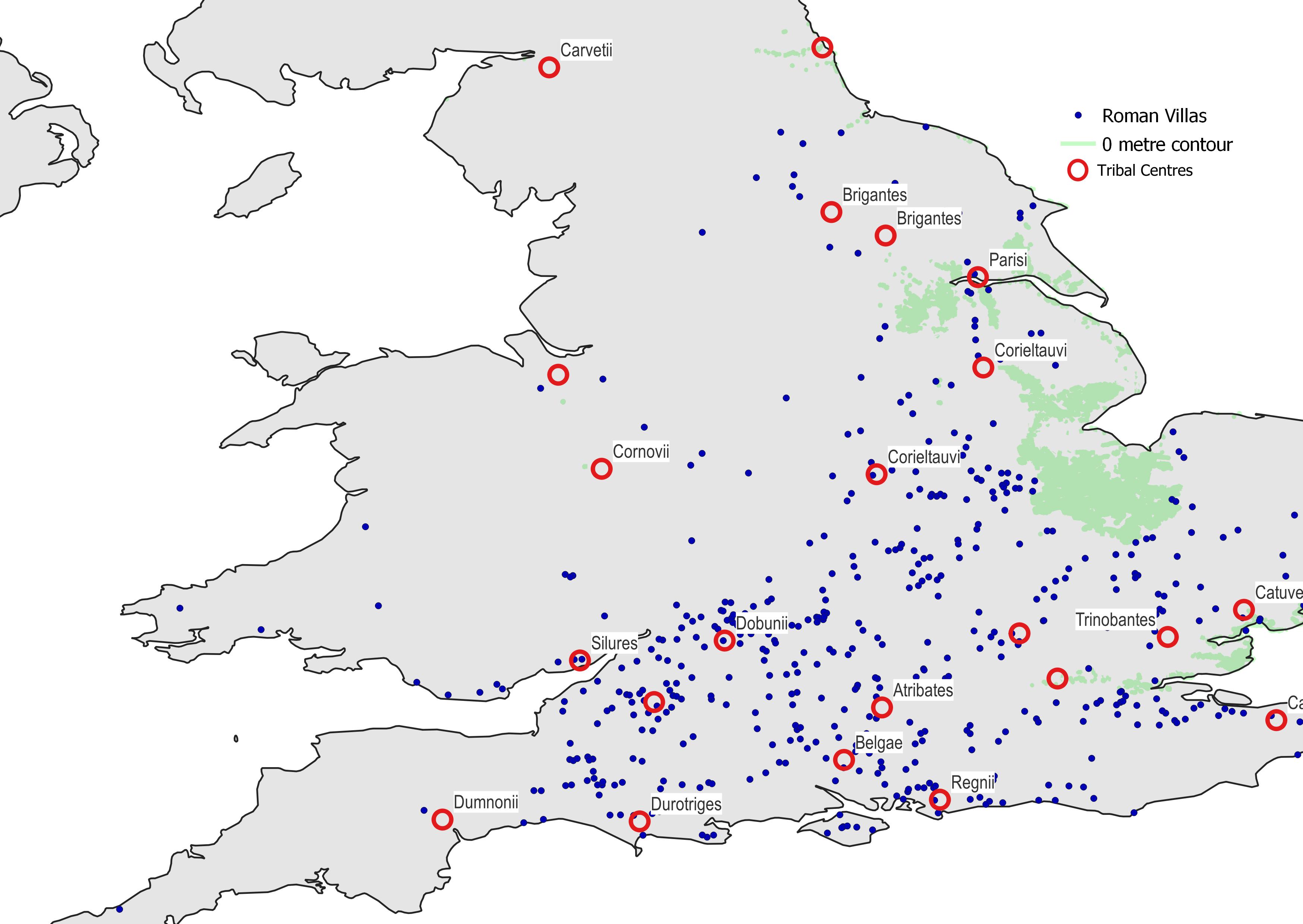

So, how to account for this absence of villas even where conditions were favourable? We know that British tribes frequently fought each other. Stuart Lacock describes continuing tribal warfare even during the Roman occupation. We also know that some of them fought against the Romans (who invaded in 43CE). Hatred was particularly intense between the Romans and the tribes of East Anglia, dating back to the uprising of Caractacus, not long after the Roman occupation. Caractacus (died c 50CE) was active for twenty or so years. Also in East Anglia the Iceni revolted in 47CE. From 60CE to61CE the Iceni were again at war with Rome. Within 20 years of the Roman occupation, all of East Anglia had fought, and nearly defeated the Romans. The Silures (also under Caractacus) were engaged in protracted warfare with the Romans, starting in 48CE and not finishing until about 75CE. The Brigantes were the major British tribe of what was to become Northern England. They were the last of the major tribes to be subdued. It didn’t help that they were internally divided as husband and wife vied for power.They fought Rome for more than 100 years from 47CE to 155CE. In Cornwall, the Dumnonii exchanged minerals for self governance. The Cornovii (in the West Midlands) don’t fit into this pattern. There were few Romano British villas in their lands but this was not because of bad feelings with the Romans. They quite quickly accepted Roman rule and with about 14,000 inhabitants, Viriconium (Wroxester) was the fourth largest city in Roman Britain. The eratic nature of rebellions could account for the patchy distribution of Roman Villas.

Warfare between Britons and Romans was deep rooted. In c. 100 Tacitus wrote:

“Formerly they (the British) were ruled by kings, now they are separated under the leadership of chieftains in factional quarrels. Nor is there anything advantageous for us against these most powerful tribes than the fact that they do not consult for the common weal. Rarely do two or three tribes join for averting a common danger; and so while they fight as individuals, they are overcome as a whole.” (Edward P Cheyney, Ginn and Company 1908, 18-19).

The situation was the same 400 years later according to the British monk Gildas.

“For it has always been a custom with our nation, as it is at present, to be impotent in repelling foreign foes, but bold and invincible in raising civil war …”. (Gildas and Pearce 2003, Section 21)

It would have been nice to map out the distribution of villas against the geography of the British territories to see whether they were associated. However, there was little evidence on the geographical extent of the tribes. In many places, the best I could do was to use the tribal capitals to indicate the possible position of the tribal lands. This is shown in Figure 2, which also shows the density of Roman villas by county.

Figure 1 Showing the Distribution of Roman Villas in Relation to Tribal Centres |

The history of the Iceni is particularly well documented, for which we have Tacitus, probably the most famous Roman historian, to thank. He could hardly have been in a better position to talk about what had happened. His father-in-law was Agricola, a general and a tribune to Suetonius, the Governor of Britain at the time of its subjugation. Rome’s treatment of the Icenii was extremely brutal.

Rome had always ruled by a combination of fear and favours. It could make friends with rivals or it could ruthlessly destroy them. By 60CE, most of the tribes in southern Britain had been subdued. Suetonious Paulinus had recently been appointed governor. The fertile island of Anglesey remained independent. The new governor decided to make his mark by taking it. After initial setbacks, the Roman troops rallied and, according to Tacitus,

“…bore down on their opponents, enveloping them in the flames of their own torches” (Edward P Cheyney, Ginn and Company 1908)

At about the time of this blood lust, news came of a rebellion by the Iceni who lived in what was to become Norfolk. Prasutagus their king had died. He had previously offered to divide his Kingdom between the Emperor Nero and his two daughters. But, Paulinus was a new Governor. Perhaps he wanted to dictate his own terms, perhaps he remembered the recent rebellion of the Icenii, only a decade or so earlier. He was the victor of Anglesey and was not going to be told what to do by his subjects in the East. It sounds as though he over-reacted. Again, according to Tacitus,

“…… kingdom and household alike were plundered like prizes of war, the one by Roman officers, the other by Roman slaves. As a beginning his widow Boudicca was flogged and her daughters raped. The Icenian chiefs were deprived of their hereditary estates as if the Romans had been given the whole country. The king’s own relatives were treated like slaves.” (Edward P Cheyney, Ginn and Company 1908).

with the Trinobantes (to the South) so all of East Anglia was now in arms. They destroyed Camulodunum (near modern St Albans) then London. Tacitus put the dead at 70,000. But retribution followed retribution. When the Roman army had been reinforced, the ensuing battle killed 80,000 British while more died from starvation in the ensuing peace. These wounds would leave a scar that lasted for generations.

As well as the distribution of Roman villas, there is also some circumstantial evidence from pottery excavations. A lot of work from the mid twentieth century was undertaken by JNL Myres. He was the Librarian at the Bodleian Library in Oxford; an expert in early Anglo-Saxon history; and author of the section of the Oxford History of England that deals with the Anglo-Saxon settlement (J. N. Myres 1986). What I found really interesting was his idea that the Anglo-Saxons arrived well before the Roman departure, as Roman mercenaries. He (J. N. Myres 1969, pp 71-72) based this on the discovery of Anglo-Saxon pottery in the major cremation cemeteries of the mercenaries who were garrisoned by the Romans in eastern England. The way he describes their billeting arrangements sounds more like an army of occupation, than a protective force, the absence of Anglo-Saxon archaeology in the nearby towns suggesting that they didn’t mix with the locals (J. N. Myres 1986, p 99).

So, although the soldiers lived, and buried their dead outside the towns, they didn’t mix with the locals in the towns (J. N. Myres 1986, p 99). perhaps implying hostility between the locals and the representatives of Rome.

When the Romans left, the mercenaries, reinforced by clan members from back home, spread out to the West and South. Myres tracked their expansion by following finds of their distinctive “buckelurnen” pottery until they peter out in Warwickshire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire. He believed that this showed a temporarily revival of British power following the battle of Mons Badonicus c. 500CE (J. N. Myres 1969, pp 110-111). (The British forces were famously led by Ambrosius Aurelianus.) This supported the account of the British monk Gildas (Gildas and Pearce 2003).

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tracks the places that Wessex conquered. It wasn’t until 530 they took the Isle of Wight from the British, and even later when Wessex “took four towns, Lygean-birg [Lenbury], and Ægeles-birg [Aylesbury], and Bænesington [Benson], and Egonesham [Eynsham]”.

So, how did some Britons manage to resist the rampaging mercenaries? Again the distribution of Romano-British villas might help explain. These were most heavily concentrated in the lands of the Dobunni, around Cirencester (the tribal capital), Gloucester, and Bath, lands that were to become part of the Kingdom of Wessex (see Figure 2).

FIGURE3 ABOUT HERE Figure2 xxxx

There is even evidence of a prosperous post Roman villa, with a new mosaic floor, at Chedworth, 8 miles north of Cirencester (Milligan 2020). Clearly the region did not roll over at the first whiff of a barbarian insurrection. Even if not all villas continued to operate, the land would have been “in good heart” with a long history of cultivation. The withdrawal of the Roman troops at least had the advantage that there was no need to pay Roman taxes; the rich agriculture itself could support a military class or pay for mercenaries. The area not only had a developed agriculture, it also had the remains of fortified towns to offer some protection.

It was not until 577 that Gloucester, Cirencester and Bath, possibly in the lands of the Dobunni (see Figure 2) were eventually captured. This was 150 years after the Roman departure (J. N. Myres 1969, p 117). I would like to think that, as the Anglo-Saxons conquered the lands of the Dobunni, they took over their political organisation and culture. To incorporate it into their own state of Wessex. The only evidence I have to support this rather bizarre hypothesis is that the early Kings of Wessex had Celtic names – Cerdic, Ceawlin and Caedwalla. So, perhaps the conquest of the lands of the Dobunni involved the assimilation of their genealogy into that of the Kingdom of Wesssex.